Nuria Ros, PhD in psychology, tells us in the first person about her educational stage; the undiagnosed dyslexia marked her passage through school and life. Fortunately, and after an ordeal, with great tenacity she managed to overcome adversity. A true resilient.

“It’s 9 o’clock, it’s time to enter the classroom. I try to go unnoticed in the middle of the line. Inevitably I am already inside sitting at the assigned desk. Voices, laughter, throwing balls of paper… The teacher calls for order from her platform. Silence, and the military chanting of the roll call begins. State of tension, and like every day when my last name is reached, already automatically and unconsciously, I get lost under the chair looking for the fallen rubber and barely a thread of voice emerges with a ‘present’, with my face as red as a beet. Dry throat, thick saliva and consistent problems swallowing. The torture is only in its preamble. The cast was long and the passage of time until leaving school even longer.

Homework review, explanation of the “letters”, of the “numbers”, reading… abundant reproaches and punishments for what concerned me. Then I was six years old and it was understood that the basic foundations of reading and writing and calculation, had been acquired at home. In fact, my family tried hard to do it, but “threw in the towel”, concluding that unlike the “brilliant older brother that I got in the distribution”, “the rare, clumsy and slow-witted” that I was, would have to be kept in school until she was twelve years old so that she could obtain the minimum title of the moment and then put her to work as an apprentice in a factory. A promising future.

I spoke little and listened a lot. I had as good auditory memory as bad visual memory. I remembered perfectly, unless I was hidden in my world of fantasy and imagination and had not paid attention. It is true that they brought me back to reality quickly with some taxative system, whether it was a shout with an insult or directly a slap.

The teacher of that first year, with a high probability close to retirement, was a devoted follower of the pedagogical method of “spare the rod and spoil the child” and practiced it diligently. Unfortunately, the progressive geometric increase of stabs and derogatory qualifiers did not make the vowels easier for me, nor the damn consonants, and let’s not even talk about joining them in syllables and reading them.

I felt vertigo and literally panic when they forced me to go up to the pulpit to “read” before the class. I swear I tried to identify that gibberish called letters, but I couldn’t. I stammered, tried to guess… and already watched out of the corner of my eye the reaction of the teacher and the laughter of the esteemed peers.

One of the most recurring phrases was “look what is written”, and I looked but it was as if I didn’t see. Another experience that also gratified my soul was copying on the blackboard. It could have been said that my writing was Chinese, and the kind teacher only dedicated flattering epithets to me, the mildest being “clumsy and stubborn”.

For the other children everything was or seemed simple, including learning the days of the week, the alphabet, the months of the year, the series of concepts… for me it was an enormous mystery. In that historical period it was “well considered” to call a child who did not learn to read and write, a donkey and mentally retarded.

I couldn’t manage to hit the left and right either, nor make the numbers with “the bellies” in the required direction. Other usual compliments were “disaster, dirty, messy”. I put effort in although I couldn’t organize myself. They made me repeat first grade, although nobody had good expectations about me.

I felt a lot of shame, withdrawal, I was not like the others. Nobody believed in my possibilities and neither did I. I was not popular nor did I have little friends, apparently it was not convenient for the others to get together with me lest stupidity be contagious.

I had had disruptive, impulsive, explosive behaviors, feeling of impotence and despair, conveniently reprimanded both at school and at home. They said I was lazy, undisciplined, rude, disobedient…

Without knowing how to explain it, I was aware of being in the most absolute solitude. I proposed secretly and stubbornly to learn the letters as it were, they were the key. It occurred to me to trace each one of them, in the same way with the numbers, in the mud of the street, first with my eyes closed, forming them and feeling them with my fingers and then looking at them. I started with mud, then with flour and plasticine, and I even did it with my mother’s only and greasy lipstick on a mirror. This last thing cost me a few blows. But I made it.

The light came on for me, the aha!, to be able to identify grapheme with phoneme. I could finally read. I overcame the repetition of first grade and in second grade I found a great prize, Dña. Araceli, and of her I do say the name, “the altar of heaven”.

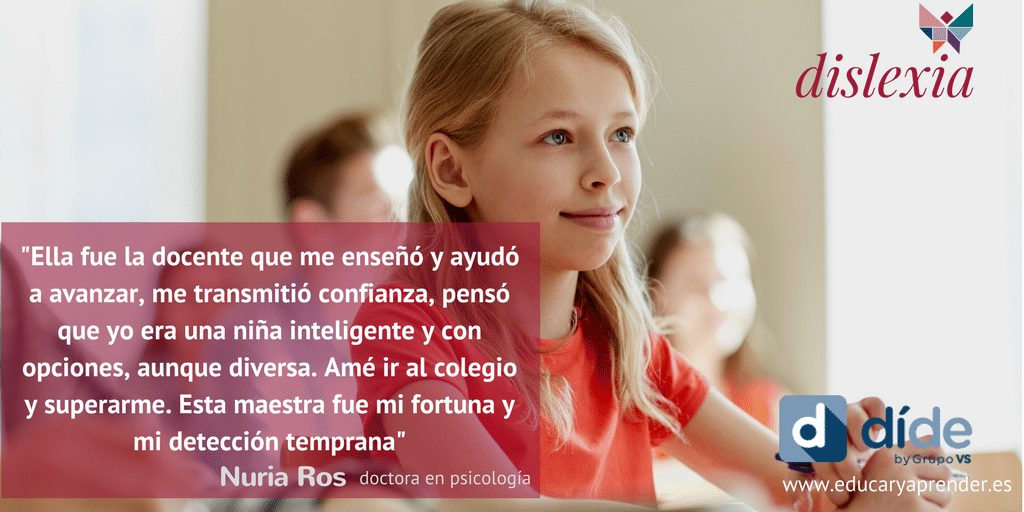

She was the teacher who taught me and helped me to advance, she transmitted confidence to me and of course she thought that I was an intelligent girl with options, although diverse. I loved going to school and improving myself. Then nobody spoke of dyslexia. This teacher was my fortune and my early detection.

The challenges did not end here, I stumbled with spelling, with great incomprehension of the accents, with grammar, with perspective, with spatial orientation… with almost thirteen years my essays were painful, I was the queen of juxtaposed phrases and some coordinated.

Progressively and with a lot of personal work, I was obtaining the “Eureka” and connecting.

Learning other languages is an arduous task, especially in what concerns spelling and grammar.

I discovered in the university stage that all the ordeal related, had its origin in what is called dyslexia.

At present there are very different and more suitable circumstances, even so the best result for the adequate evolution of the child is an early detection not left to occasional fortune, to be able to face conveniently and satisfactorily the possible obstacles.

A program like díde, in addition to detecting a difficulty such as dyslexia early, also offers the possibility of pointing out other indicators, carrying out a convenient and facilitating screening for the success of the development of the minor”.